China is scanning U.S. political targets. Who should care?

A recent FBI warning to Republican and Democratic party leaders about suspicious scanning by Chinese hackers left some researchers scratching their heads.

Last month, the FBI warned political party leadership in several U.S. states that China-backed hackers were scanning their networks ahead of the Nov. 8 midterm elections. Less clear was what anyone should do about it.

The Washington Post reported in October that “Chinese government hackers are scanning U.S. political party domains ahead of next month’s midterm elections, looking for vulnerable systems as a potential precursor to hacking operations, and the FBI is making a big push to alert potential victims to batten down the hatches.”

It’s not clear what prompted these warnings, and the FBI hasn’t publicly acknowledged them even as it published a pair of press releases about its other election security efforts. The murkiness surrounding the alerts highlights the challenges facing the federal government as it tries to relay cybersecurity intelligence to a wider audience that can act on it. And the episode raises questions about just how much evidence of “scanning” can really say about a cyber adversary’s intentions and capabilities.

“I scratched my head” at the FBI’s warning, GreyNoise vice president of data science Bob Rudis told README. “I usually will snark on Twitter, but this wasn’t even snark-worthy. It just doesn’t make any sense, and if it’s not snark-worthy for me, that says a lot, because I’m a low threshold snarker.”

FBI officials told The Washington Post that “none of the potential targets were hacked or breached.” (The FBI didn’t respond to README’S request for comment.) There’s also no indication that politically affiliated networks were compromised in the weeks between the publication of that report on Oct. 17 and the midterm elections held on Tuesday.

So why make a fuss about scanning?

Scanning is not inherently malicious

It’s been nearly a decade since CNN breathlessly declared Shodan, a service that allows users to find networked devices and learn what software they’re running, to be “the scariest search engine on the internet.” The outlet described Shodan as “a kind of ‘dark’ Google, looking for the servers, webcams, printers, routers and all the other stuff that is connected to and makes up the Internet.”

While this kind of scanning may have seemed scandalous in 2013, it’s common practice in 2022. Companies like Shodan and Censys are constantly probing internet-connected devices for public-facing data. In some cases, that information is used by threat actors looking for their next target. In others, it’s used by researchers looking to defend these devices.

“People have terribly configured things facing the internet,” Rudis told README. “State governments do. City governments do. Giant corporations do, tiny corporations do, everybody’s got garbage facing the internet because everybody is busy and updating things is hard. So just saying ‘Hey, we saw people scanning the internet for something,’ that’s important. And that’s why we do what we do.”

GreyNoise typically warns customers when threat actors start to scan for particular vulnerabilities but doesn’t make a fuss about everyday scanning. Misconceptions about this kind of activity still abound, though, and Rudis said that when he was at the Rapid7 security company, the firm constantly received opt-out requests and complaints from entities being scanned.

“To be able to give you that external view of what attackers are going to see about you is a really great perspective to have,” Rudis said. “And then when you suddenly go ‘scanning is bad’ in general, and just always cast a bad light on scanning, it really makes organizations not want to have that happen, not want to take advantage of those things, when they really should be taking advantage of those things.”

Consider the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) announcing Monday that it would be scanning practically every connected device in the U.K. This could attract criticism due to NCSC’s relationship to the GCHQ intelligence agency, but the NCSC was clear that it’s doing this scanning to improve the country’s security, “not trying to find vulnerabilities in the UK for some other, nefarious purpose.” (Emphasis theirs.)

NCSC also said that anyone opting out of this scanning was free to do so, but warned that “if you do opt-out, we’ll be limited in how we can help you understand your cyber security exposure.”

Scanning can provide valuable information outside the UK as well. When the pair of vulnerabilities in the OpenSSL cryptographic library were announced earlier this month, for example, Censys was quick to report that only 0.4%of the 1.8 million hosts known to be running OpenSSL were affected by the flaws. That can be valuable context for anyone worried about the impact of a particular bug.

Unpacking the FBI’s attribution

You can’t throw a rock at a cyber threat intelligence conference without hitting someone who takes attributing malicious activity very seriously.

But it’s notoriously difficult to attribute a cyberthreat to a particular threat actor — or even to a specific country — because the cyber domain presents ample opportunities to mislead investigators.

When it comes to scanning, it’s easy to obfuscate the origin of this traffic by using a virtual private network or the Tor network. Consumers take advantage of these capabilities to access different Netflix catalogs available to other countries; threat actors use them to cover their tracks.

“There isn’t a single nation-state entity that I’m aware of that is deliberately going to use an identifiable nation-state resource” to conduct scanning, Rudis said, or any other kind of cyber operation.

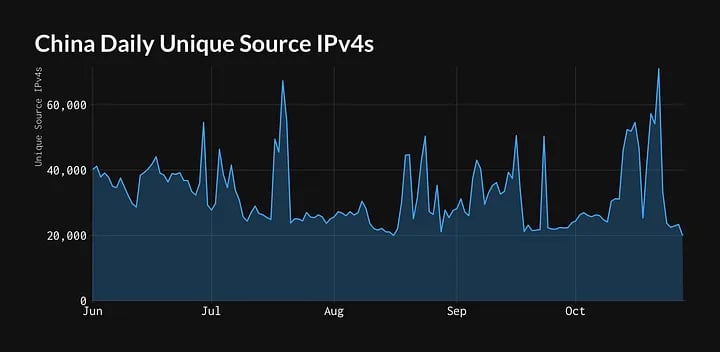

GreyNoise shared data with README indicating that activity within China’s IP range did increase in the weeks before The Washington Post’s report. The data showed similar peaks in previous months, however, and a company spokesperson told README that “nothing about this spike seems unusual.”

Attributing that activity to the government in Beijing is another matter altogether.

“Our researchers can’t tell you whether it’s a nation-state doing that or not,” Rudis said. “Because there’s just no ‘nation-state flag’ bit that you set on a packet that says ‘Oh, yeah, this is coming from here.’” And even if there was, threat actors would be as quick to spoof these bits as they are to use VPNs and Tor.

Rudis pointed out to README that it’s “weird” seeing the FBI discussing nation-state level scanning activity when much of its focus tends to be on cybercrime. But it’s possible the FBI received critical information about suspicious Chinese activity from elsewhere in the intelligence community.

China threat looms

The FBI’s warning fits with the U.S. government’s broader efforts to warn about increasing competition from China in the months ahead.

It also arrived as misconceptions about common activity, from scanning to distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attacks, continued to spread. China scanning Ukrainian networks was mischaracterized as the country launching thousands of cyber attacks on Russia’s behalf, for example, and in some cases DDOS attacks on airport websites in October were mistakenly covered as attacks on the airports themselves.

There is a significant difference between scanning a network and conducting a cyberattack. A DDOS attack might count, but even those are often easy to mitigate, with most organizations being able to bring their websites back up shortly after the attacks begin.

Gen. Paul Nakasone, the head of the U.S. Cyber Command (CYBERCOM) and the NSA, said in September that “we see scanning all the time” when Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency director Jen Easterly mentioned “an uptick in reconnaissance” on critical infrastructure since Russia invaded Ukraine.

Nakasone and Easterly each warned about China during their talk with the Council on Foreign Relations, and several days later, the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy for 2022 focused on the government’s concerns about Beijing as well.

“The PRC is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it,” the White House warned.

And, yes — at least some small part of those plans includes scanning.