NIST vulnerability bottleneck underscores fragility of software security

Illustration: Si Weon Kim

A sudden halt to the ranking of vulnerability severity has left government agencies and some companies without an approved source of ranking and prioritization.

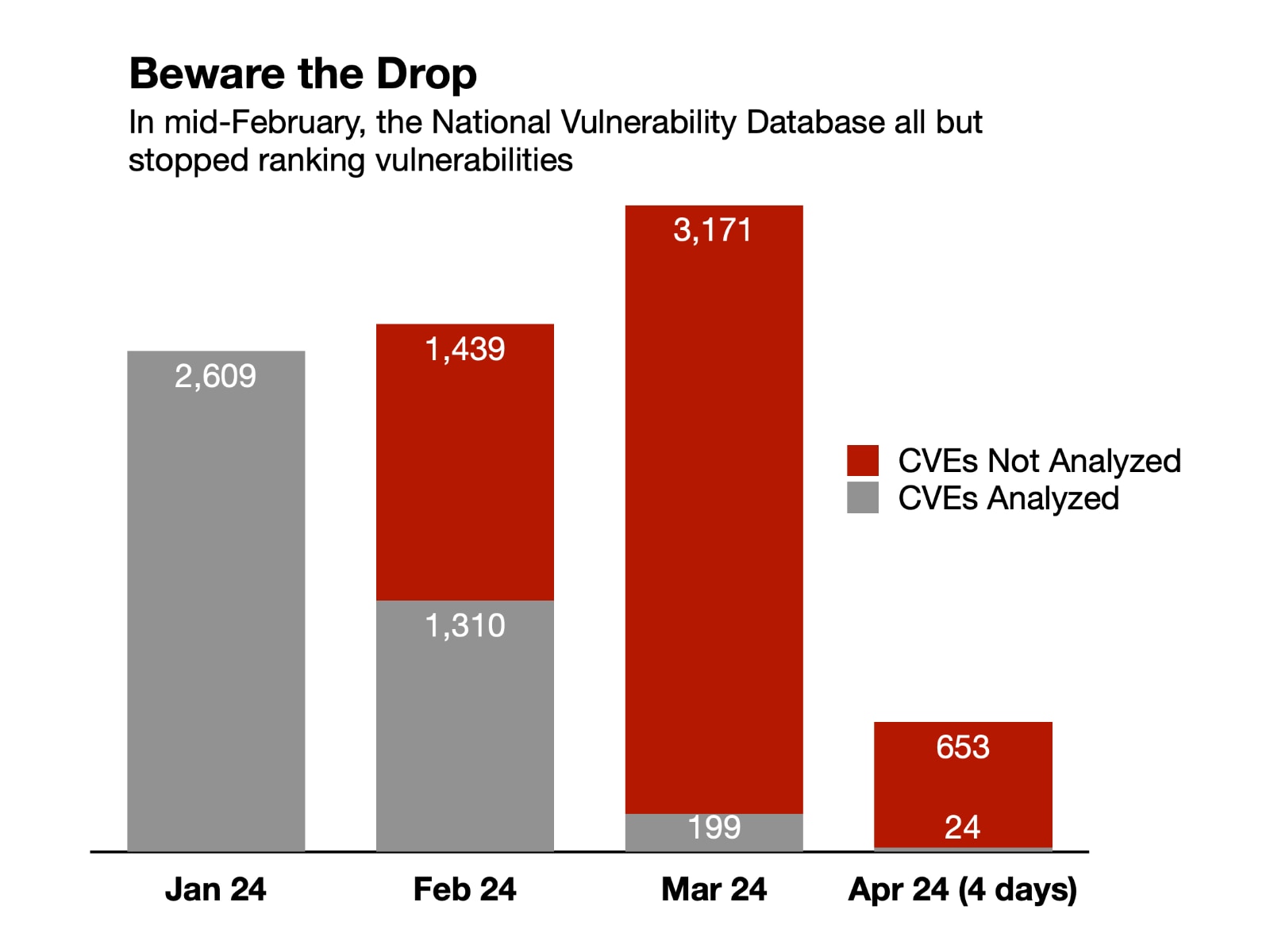

In mid-February, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) suddenly stopped—or significantly curtailed—rating the severity of security flaws tracked in the National Vulnerability Database (NVD), currently used by U.S. government agencies, private companies, and other organizations to agree on the severity of a given vulnerability and—as a result—how they should prioritize updates to components of their tech stacks.

At the VulnCon cybersecurity conference in late March, NIST program managers said that a "perfect storm" of challenges—including budget issues and a contractor's completion of their work—led to the agency's failure to keep up.

Yet, the lack of an agreed-upon source of vulnerability-severity information has left cybersecurity teams and vendors at a loss, Chainguard CEO Dan Lorenc told README. Companies required to comply with federal regulations have been the hardest hit by the lack of additional information added to vulnerabilities in the NVD, but the change has also affected the entire cybersecurity ecosystem to varying degrees.

"We're incredibly ill-equipped to deal with a major vulnerability right now," he said. "If a new Log4Shell or some other issue appeared — even worse if it were in some proprietary software — we'd be incredibly unprepared to deal with them."

Fig. 01 — Starting in mid-February the National Institute of Standards and Technology essentially stopped enriching vulnerabilities with metadata, including the severity scores. Red represents vulnerabilities whose severity is not verified. Source: NVD Dashboard

NIST originally acknowledged the problem with little more than a terse alert on top of its website. The agency offered additional information with a March 29 statement in which it blamed the issue on a variety of factors, including “a change in interagency support.”

"Currently, we are prioritizing analysis of the most significant vulnerabilities," NIST said on the NVD's announcement page. "In addition, we are working with our agency partners to bring on more support for analyzing vulnerabilities and have reassigned additional NIST staff to this task as well."

Continued stress on vulnerability information infrastructure

The issue comes as the number of vulnerabilities disclosed weekly continues to surge. In 2023, more than 28,800 vulnerabilities were disclosed and assigned a Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) identifier, increasing by more than 15% compared to the previous year.

In fact, since MITRE expanded the number of organizations that could assign CVEs in 2016 and established a system of CVE numbering authorities (CNAs), the annual number of reported vulnerabilities has grown between 5% and 25% each year. (The first year, with the organizational dam removed, saw the number of vulnerabilities more than double.) Much of this is due to more CNA organizations issuing CVEs for the software under their purview, with the number of CNAs growing from 22 in 2016, to 114 in 2020, to nearly 370 today.

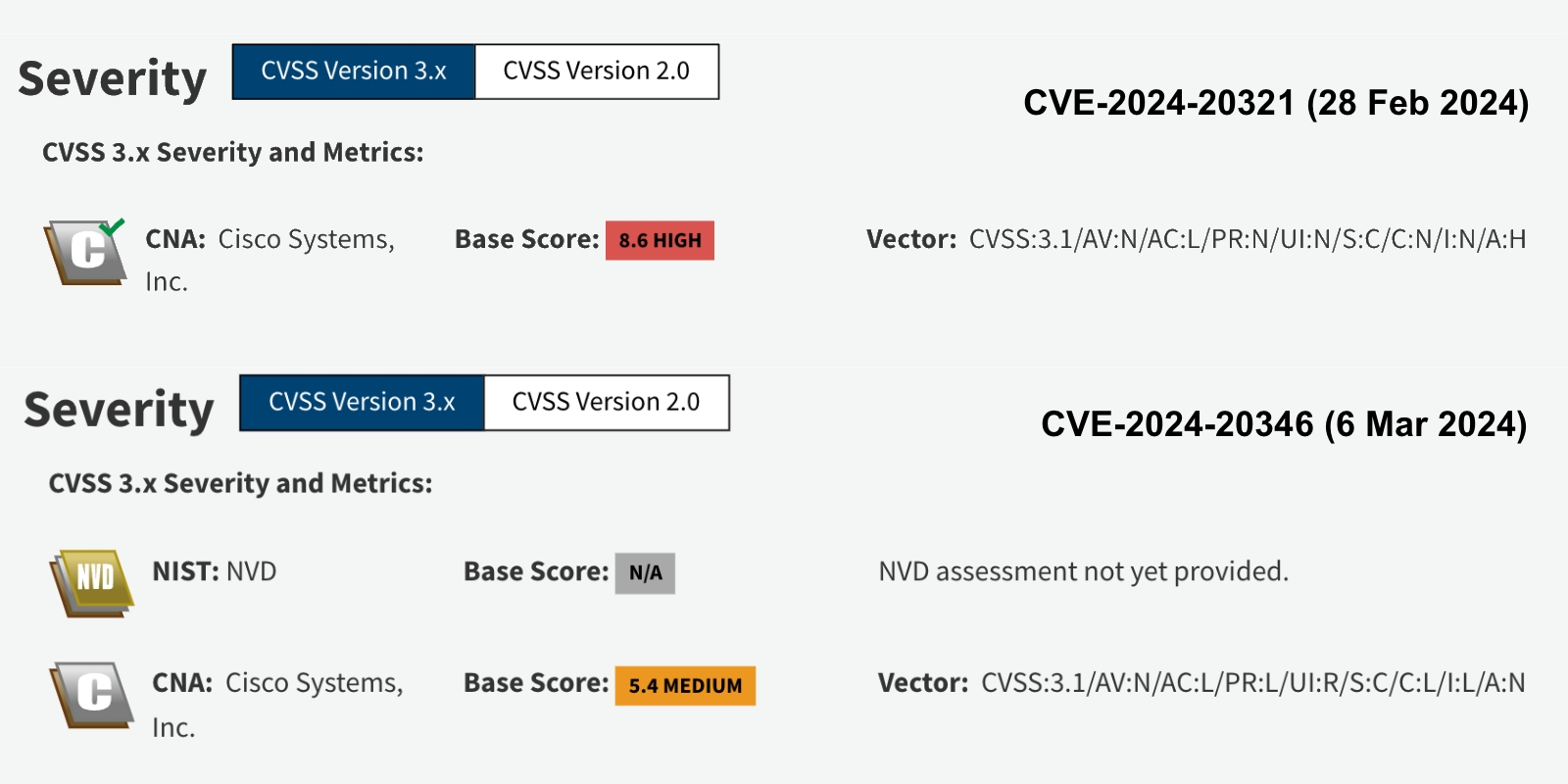

While creating the CNA system removed the initial block that prevented the logging of vulnerabilities, the review of CVSS scores by NIST has resulted in a different kind of block. Typically, the National Vulnerability Database enriches information about reported vulnerabilities, adding, for example, Common Product Enumeration (CPEs), Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) scores and Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) information that security professionals use to get better insight into the vulnerability’s potential impact.

Some CNAs and threat intelligence providers also enrich CVE information, but these organizations are typically siloed and don’t necessarily use the same methods to determine a vulnerability’s severity, Josh Bressers, vice president of security for the Anchore software supply-chain security firm, told README.

"Literally, no one is cooperating, and the only way we can solve a problem of this magnitude is by working together," he said. "We might be able to put some Band-Aids on it and maybe limp along for a little longer, but just the rate of growth we have— it's going to crush everyone, if we're not cooperating and doing it right."

NIST is working on creating a consortium of government agencies and private companies to oversee the review of CVSS scores and metadata enrichment for vulnerabilities, but so far details have been scarce. "Although the official paperwork is not out yet, NIST has every intention of putting together the NVD Consortium to make the NVD more relevant in the future," NVD Program Manager Tanya Brewer told Infosecurity Magazine. "It should be operational within two weeks."

Reliable scoring of vulnerability is critical

Cybersecurity vendors and researchers are not waiting. On April 5, dozens of members of the vulnerability-reporting community published a letter to Congress stating that the additional information and metadata provided by the vulnerability information-enrichment function of the NVD are critical.

"At a time when we and our colleagues are working to hold back a devastating tide of ransomware and the widening intrusion of foreign intelligence and military organizations into American critical infrastructure, those who protect America’s critical infrastructure are being stripped of a vital resource," the letter stated.

Alternatives could exist. In 2021, Google introduced the Open Source Vulnerabilities (OSV) database as a way to start fixing the problems of enriching information for vulnerability reporting in open-source projects. While OSV is not designed to be a replacement for the NVD, vulnerabilities in open-source software that could be covered by the OSV currently account for about a third of the NVD, and it works to describe those issues, Google senior software engineer Oliver Chang told README.

"The mechanisms developed for CVE did not work well for the modern practices and workflows of open source," he said. "CPEs understandably make sense for proprietary software, but open source has a lot of unique properties that make this approach suboptimal. In particular, mapping CPEs to open-source dependencies was often error prone and difficult to do at scale."

Fig. 02 — A tale of two vulnerabilities: One vulnerability (CVE-2024-20321) gets a severity score in late February, while the other (CVE-2024-20346) is waiting on an NVD assessment. Source: National Vulnerability Database

While a consortium of organizations contributing to a single database, such as whatever succeeds the NVD, could be a viable path forward, another option could be a group of database efforts, such as the OSV, working together to ensure complete coverage. Using efforts, such as OSV, as a federated partner could work to alleviate part of the workload that NIST must deal with. By moving the work of triaging vulnerability information closer to the open-source maintainers, for example, a federated group could remove some of the burden of keeping up with the deluge of vulnerabilities, Chang said.

"A publicly funded resource, which is single-handedly responsible for triaging all vulnerabilities for the entire industry, unfortunately does not scale, especially as the industry continues to grow," he said. "A more open and federated approach will likely work much better in the long run."

An uncertain future for official rating system

Anchore’s Bressers said that despite these potential alternatives, however, the NVD has something the other databases do not: a federal mandate. He noted that the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) requires that data from the NVD be used to evaluate vulnerabilities.

"Even though there's a bunch of alternative datasets — and many of them are very, very good — there are a whole bunch of federal compliance standards today that specifically call out NVD ... as the source for vulnerability-specific information," he said. "What does it mean, if you're trying to comply with FedRAMP, and there's no NVD data now, but FedRAMP specifically says you should be using NVD data?"

NIST said in the March 29 announcement that it’s committed to supporting the NVD and plans to organize a public-private consortium to maintain the vulnerability rating verification system.

Meanwhile, private-sector firms are looking to bolster the program and find a more resilient approach to verifying the severity of software vulnerabilities.

"[The NVD is] something everyone was relying on, but nobody knew they were relying on it and now falling over and suddenly bringing attention to the issue," Lorenc said. "Sometimes it takes a system to disappear for everyone to realize how important it actually was."