Home is where the hackers are: The dizzying task of securing remote work

Increases in phishing attacks, credential stuffing against corporate cloud services and unpatched vulnerabilities in consumer hardware have all skyrocketed since the COVID pandemic upended work routines. With more employees logging in from home, locking down workers’ security habits and local networks has never mattered so much.

With more employees working from home, companies need to pay more attention to security. Just ask LastPass.

Between August 12 and October 26 last year, unknown attackers managed to breach the company’s systems and access LastPass’s code repositories, internal scripts and documentation. The attackers then used the information to successfully compromise the home computer of a critical employee: One of four DevOps engineers who had access to the company’s crown jewels — the sensitive data for LastPass’s cloud infrastructure, including configuration data, API secrets, authentication seeds and customers’ password vaults, albeit encrypted in most cases with the user’s private password.

The attack involved “targeting the DevOps engineer’s home computer and exploiting a vulnerable third-party media software package, which enabled remote code execution capability and allowed the threat actor to implant keylogger malware,” LastPass said in a February statement. “The threat actor was able to capture the employee’s master password as it was entered, after the employee authenticated with MFA (multi-factor authentication), and gain access to the DevOps engineer’s LastPass corporate vault.”

With remote and hybrid work here to stay, the breach shows the dangers of pandemic-era work trends. Without the traditional perimeter defenses that surround office networks, remote workers and their home networks have dramatically expanded businesses’ attack surface areas, putting companies in peril, experts told README.

Relying on workers to make security decisions and keep their infrastructure up to date can be fraught with risk. Although cable-modem and router security has improved, exploited home routers are often used by attackers as a jumping-off point for attacks against other targets, because the devices are not regularly updated.

In 2022, for example, Japan’s Public Security Bureau warned consumers that a spate of router compromises had been used as beachheads for further attacks, according to the Mainichi newspaper. In December, researchers discovered attackers had infected home and small-office routers based on MIPS processors with malware, from there infecting systems connected to the compromised routers.

Embracing remote workers also means increasing the adoption of cloud services and infrastructure. Companies have shifted many business systems and processes to the cloud, leading attackers to focus on compromising the weakest point in cloud infrastructure: Identity. Stealing employee credentials or piggybacking on their connection to a cloud network — as happened in the LastPass case — can lead to significant compromises of corporate infrastructure.

Finally, removed from adequate monitoring, the remote worker can often be the weak point in a company’s overall security posture. Phishing emails can lead to credential theft or to the compromise of workers’ home computers, which can then be a portal into the corporate network.

Mark Loveless, a staff security researcher at software services firm GitLab, which has an all-remote workforce, finds that new employees — especially those who come from an office environment — often bring bad habits, he told README.

“Office workers normally are used to just going into an office and sitting at a desk behind a nice, comfy firewall, where they are protected, because they are on a corporate machine in a corporate environment,” he said. “When they become remote workers, any bad habits they had were replicated at home, and any bad habits they had using computers at home, which could be absolutely atrocious, may bleed over because it’s convenient and easy.”

Hybrid work is the future

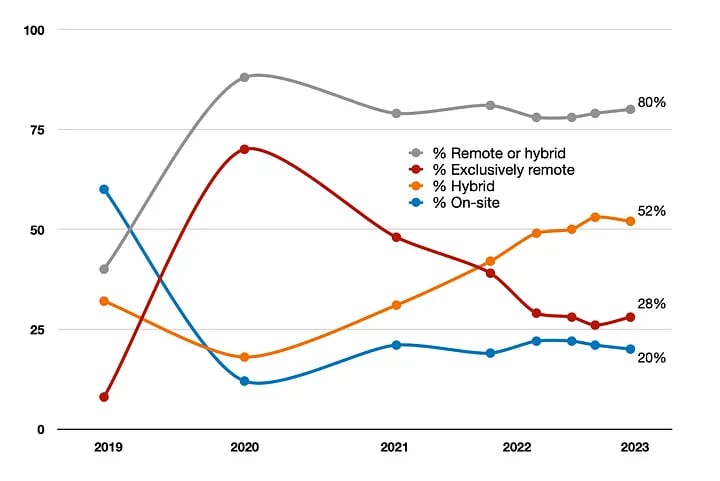

While the Biden administration has declared an end to the U.S. national emergency in response to the COVID pandemic, remote work — and its inherent risks — is here to stay. The share of U.S. remote and hybrid workers doubled to 80% as of February 2023, compared to 40% prior to the pandemic for remote-capable positions, according to pollster Gallup. During the pandemic, the number of exclusively remote workers in this category peaked at 70%, up from 8% in 2019, and remains high today at 28%, the survey firm found.

Unfortunately, companies still have not fully transitioned to security architectures and processes that can protect their far-flung endpoints. Only 15% of companies reported having the advanced maturity in their security processes necessary to secure remote workers, despite the vast majority (86%) voicing worries that their companies would suffer a business disruption due to a cybersecurity incident, according to Cisco’s Cybersecurity Readiness Index released in March. The index scored companies on their security preparation in five areas — identity, devices, networks, application workloads and data security. Overall, 8% of companies were considered beginners, 47% in a formative stage and 30% progressive, while only 15% scored in the most secure grouping.

“While these security areas are equally crucial, progress is not even across all five pillars,” J. Wolfgang Goerlich, advisory CISO at Cisco Secure, told README. “Identity Management — recognized as the most critical area by our respondents — still has room for improvement, with around 58% of respondents finding themselves in [only] the early stages of security readiness.”

More advanced attackers have taken notice

Sophisticated attackers know that home is where the vulnerabilities lie. The compromise of the LastPass engineer’s home system is not the first time that a major organization has been affected by a cyberattack on a particular employee. In 2017, Russian hackers reportedly stole classified documents and offensive tools by compromising a National Security Agency (NSA) contractor’s home computer. In 2022, attacks using the credentials of hybrid workers at game developer firm Rockstar Games and collaboration firm Slack led to significant compromises of enterprise infrastructure and intellectual property.

Such attacks will only increase in the future, and not just by opportunistic hackers, but by groups specifically targeting enterprises, said Phil Groce, a senior network defense analyst at Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute.

“It’s another sort of misconception that people have about the home network — that you’re going to only see opportunistic attackers primarily driven by financial motivation,” he told README. “So, the folks that are really scary, the nation-state actors, probably weren’t going to find you. But that’s no longer true, and we’ve also seen a lot of crosstalk between the two groups.”

In addition, as companies adopt cloud-native infrastructure to better support remote users, attackers are following as well. CrowdStrike said in its 2023 Global Threat Report that exploitation of cloud environments nearly doubled in 2022, for example, as attackers started targeting authentication processes and identity management tools rather than firewalls and antivirus solutions.

“Zero trust” is not just a buzzword

No wonder, then, that “zero trust” has moved from a buzzword to a necessary approach to security. Without the ability to enforce control over the perimeter and all workers’ devices, companies have had to shift their focus from trusting systems just because they are on the internal network to requiring devices and user to authenticate to services — thus, zero trust. Companies need to more closely manage identity — of people, devices and workloads — and access, attest to the security of the endpoints, monitor cloud infrastructure usage and check for anomalous behavior of trusted users and devices.

“On both the server side and the endpoint side, strategies have moved away from the idea that [the company] controls the network fabric, so therefore, [it] controls the network,” said SEI’s Groce. “We sort of started to let go of that, and I think what you’re seeing now with zero trust architecture is the evolution of that.”

Companies often start by gaining more visibility into their cloud services and embracing MFA-based identity services. Adding authentication for devices and workloads typically follows, as does looking for anomalous access to both data and codebases. In its readiness index survey, Cisco found that 58% of companies were still in the early stages — defined as beginning or just deploying — identity and access management, and 56% remained in both the early phases of protecting devices and protecting networks.

LastPass said on March 1 that it had deployed additional security mechanisms, including tightening existing privileged access controls, following the 2022 breach. GitLab’s Loveless told README that this incident — and LastPass’ response — could be a learning opportunity for other companies that have shifted to a remote- or hybrid-based work environment.

“I would say anyone with a good level of access into your company … [such as] administrative access into some of your really critical systems — they [should] have a lot more scrutiny of their actions,” he said. “They’re going to have to use an alternate account, for example, which is extremely scrutinized — everything’s logged and tracked and identified and whatnot.”

As they deploy zero-trust security, companies also need to make sure that they are approaching users’ devices and networks in a way that respects their privacy and rights, Cisco’s Goerlich said.

“The zero-trust principles have long recognized the need for providing consistent security [but also] protecting the privacy of the workforce,” he said. “These complementary goals put the emphasis on protecting the person and their devices, rather than mandating intrusive controls at people’s homes. Whatever the device — and wherever it is located — it needs to be protected.”