Inside the cloud’s digital fortresses

Cloud anthropologist Steven Gonzalez Monserrate is no stranger to the mysterious world of data center security, having studied the inner workings of the digital monoliths for years. Here’s what he found from visits in Iceland and the U.S.

The “cloud” does not live in the sky. Rather, the most vulnerable parts of our vast internet economy burrow deep underground, like rodents pursued by predators. These technologies face a dizzying array of threats, from hackers to vandals; vermin to viruses; dust particles to electrical fires; heatwaves to earthquakes.

To withstand the forces besieging our digital economy, data centers are structured more like fortresses than libraries. Some companies build their facilities in the remains of old military installations, using existing security infrastructure to insulate their data from unwanted breaches. Take the now-defunct Deltalis Radix Cloud data center in Switzerland, boring 1,000 meters into the heart of a mountain in a Cold War-era bunker that reportedly still harbors a Faraday cage for making secure phone calls. Or Verne Global’s data center campus, built in Iceland’s sprawling Keflavik naval base abandoned by the U.S. military in 2006. Others choose to construct their facilities in remote places out of sight, like the NSA’s data center complex in the high desert of Utah surrounded by an electrified fence.

As a graduate student in anthropology at Brandeis University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, I have been studying the inner workings of data centers in Iceland and the U.S. since 2015. My method is ethnography, an approach to learning about a community based on observation, participation, and the cultivation of deep relationships with the people I interact with.

As such, I have firsthand experience with the strange world of cloud security, which has become ever more important in our increasingly interconnected global economy. Given my status as an outsider in these spaces, I have been subject to a gauntlet of security protocols which vary according to the scale, size, and culture of the workplace. In most instances, my credentials had to be verified weeks in advance before I could set foot inside of a data center. With the outbreak of COVID-19, health attestations, proof of vaccination or a negative PCR test result were often required.

For colocation facilities — data centers that lease server real estate to private clients — a great deal of marketing and outreach efforts are devoted to reassuring clients that their data is safe. Just outside of Salt Lake City, the server halls of the Novva data center are patrolled by Boston Dynamics’ robotic dogs. Such measures, while effective deterrents for would-be vandals, are also valuable to potential investors or clients who value the optics of security. In this way, the image of security is itself a commodity to be sold to would-be customers. As in the natural world, an intimidating enough display can ward off even the most intrepid predator.

Guarding the cloud’s jewels

At times during my fieldwork, I questioned the wisdom of attempting to study something as well-fortified and secretive as the cloud. I had to submit my credentials for verification well in advance of screenings, sign non-disclosure agreements, submit to criminal background checks and jump through various other hoops. But that was just the beginning of a security crucible that intensified the moment I drove up to the boundary of the data center campus.

Here’s some of what I experienced, anonymized to protect the data centers I visited: By a motorized gate, an intercom box awaits me. I state my name, on-site contact, and time of my appointment. After a few minutes, a static-laden voice confirms my identity, and the gate opens, permitting me to park. In more secure settings, I have to park in a lot at a considerable distance from the facility, only to be escorted via a shuttle to the lobby of the data center campus. (This, I‘m told, is to protect against car bombs.)

I reach the lobby, passing my travel documents to the clerk who once again verifies my appointment and identity. I wait until called to proceed through a series of additional security checkpoints. Metal detectors. Fingerprint, retinal, and other biometric screenings. Sometimes, I am told to empty my pockets and leave my belongings, including my personal phone, in a secured bin to be returned upon my exit.

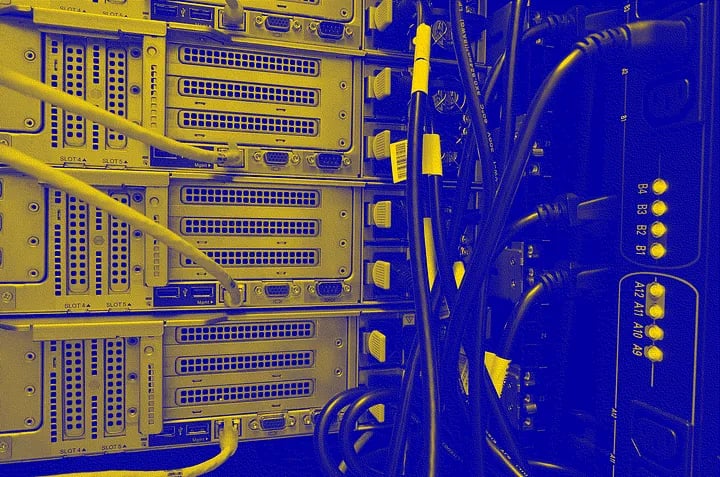

In almost every instance, I am chaperoned by a staff member for the duration of my visit. This is crucial because almost every door in a data center campus automatically locks. Sometimes there are narrow rooms with locking doors on either side called “man-traps” that prevent someone from slipping in through a door that is ajar and rapidly closing. (The common courtesy of holding the door for someone is a strict taboo in data centers.) Typically, the doors are unlocked via keycards with magnetic strips assigned to employees which provide varying levels of access to the facility depending on job description and rank.

Once I reach the facility floor, I carefully step on a sticky, adhesive mat by the entry point to remove the dust particles from my shoes. (Particulates can damage ventilation systems or computing equipment.) As I walk around the labyrinth of glittering racks of computer servers, I can see that a swarm of spherical cameras are lurking about the complex, monitoring and recording my every action. In colocation facilities, the servers of specific clients are locked in special “cages” only accessible to the clients themselves (or by select employees of the hosting company under special circumstances).

Even the technicians are closely surveilled. They spend most of their time fulfilling work orders or technical support tickets. These “tickets” are logged in a shared database and technicians are instructed to write notes along every step of the way, detailing what assets they interacted with and in what part of the facility they worked. This meticulous mapping of assets is another layer of security, as a future audit, guided by these breadcrumbs, can ascertain who was in the data center at what time and where. Such documentation is crucial for exonerating any technician who might find themselves in a situation where they are suspected of a crime.

In my conversations with data center technicians, I have found a pervasive militarized mentality. Technicians have variously described themselves as “wardens” or “warriors,” their vocation as akin to “weathering a siege.” It should come as little surprise to learn that for some data center industry recruiters, the ideal resumé of a prospective data center manager is ex-military. “Nuclear submarine officers” were especially desired, one recruiter revealed to me, because the data center, like a submarine, is a “closed system.” Recruiters also believe that the cultural cachet and moral character associated with a military background, minimize the risk of hiring someone who might be an “insider threat,” as the technicians themselves have on some occasions been known to sabotage, breach, or steal assets.

In addition to the threats posed by hackers or the thieves behind Iceland’s “Big Bitcoin Heist”, data center technicians must also protect their facilities from an array of nonhuman hazards. In data centers, rodent-traps are a common sight. In one site I visited, a family of stray cats was recruited to patrol the exterior perimeter of the campus for rodents, lured with bowls of milk and tins of sardines. Rodents, whose bodies are small enough to trudge through the plenums and ducts where live wires and optical cables are threaded, are a serious nuisance for data centers. Their propensity for chewing cabling can cause electrical fires or connectivity outages. Rodents are even a threat outside of the walls of the data center campus. In 2012, a squirrel was responsible for an outage that downed half of a Yahoo data center in Santa Clara. In one facility, bats and pigeons roosting in the ventilation ducts were dealt with by attaching grates with spikes.

Some threats are invisible, like the COVID-19 virus. A technician down can mean a server down. Others, still, like sick building syndrome are a real concern in the cool and humid climate of an air-conditioned data center. The air in these facilities must be cyclically flushed out to prevent the growth of harmful microorganisms. This same mechanism is also used to rapidly suffocate a fire before it can spread.

And then there are natural disasters. In Puerto Rico, data centers are built with seawalls to withstand storm surge. Massive diesel generators stave off the effects of power outages that follow tropical storms and hurricanes. At one of the data centers I toured on the island, such resiliency measures were enough to keep the facility running without disruption for ninety days after Hurricane Maria made landfall. Amid so much disruption to infrastructure, this corner of the cloud was a shining beacon of resiliency.

Within days, the data center had become a sanctuary. Government officials arrived, making use of the call center to coordinate search and rescue operations, supply drops, and recovery efforts in the chaotic months after the hurricane decimated the island’s infrastructure. The company decided to open the doors of its lobby to local residents desperate to charge their devices and communicate with their loved ones abroad. “We gave the people a little miracle,” a data center tech said to me.

Storms like Hurricane Maria, reveal the ways that climate change is itself a threat to our digital infrastructure. Following a record-breaking heatwave in July, London’s oracle data center suffered outages as a result of cooling system failures. Heat, if unchecked, can bring down the cloud.

Not all of the cloud is so fortified. Some data centers are found in moldy basements. Others in abandoned buildings or even shipping containers. In such facilities, there aren’t sufficient resources to offer as much protection as their more sophisticated hyperscale cousins, but the technicians who keep them afloat do their best. A padlock is better than no lock at all.