Zero-days aren't just for nation-states anymore

Illustration: Si Weon Kim

In 2023, attackers continue to wield more zero-day exploits against companies and individuals, using them for ransomware, surveillance and espionage. Will the number of zero-days climb further in the New Year? What can organizations do?

In early November, the group behind the Cl0p ransomware — variously known as Cl0p, Lace Tempest, TA505, and FIN11 — used a previously unknown vulnerability in the SysAid on-premises server to compromise systems with a web shell and malicious code.

"This is typically followed by human-operated activity, including lateral movement, data theft, and ransomware deployment," Microsoft, which discovered the threat, stated on X, formerly known as Twitter.

The zero-day exploit is not the first used by the group. In 2023 alone, Cl0p has exploited previously unknown issues in two file-transfer applications — Fortra's GoAnywhere file-sharing software in January and Progress Software's MOVEit MFT platform in May. The success of those attacks has led to the number of corporate ransomware victims growing by 143% by mid-2023, compared to the same period the previous year, according to internet services firm Akamai Technologies.

While attackers have often leveraged zero-day exploits, events of the past year has shown how effective the attacks can be, Akamai advisory CISO Steve Winterfeld told README. While phishing attacks require a hands-on approach, an attack using a zero-day exploit delivers direct access to critical resources more easily.

"You have companies paying for zero-days, you have government intelligence agencies paying for zero-days, and you have criminals paying for zero-days," Winterfeld said. "And so that market will continue to expand, and I just see some degree [of] continued growth there."

Zero-days on the rise

Vulnerabilities often belong to one of two categories: zero-days that defenders still don’t know about and “n-days” that have been publicly disclosed. There are some gray areas between those categories, however, such as whether a vulnerability reported to a vendor who silently patches it could be considered a zero-day when exploited against organizations unaware of the flaw.

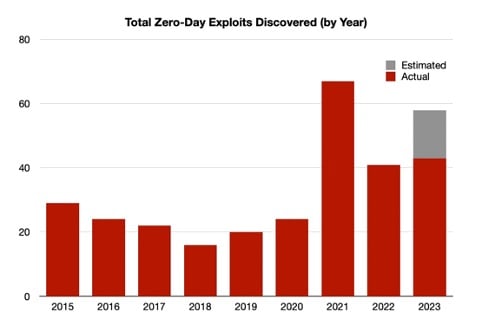

Source: Historical data ("Actual") from chart in "When Exploits Aren't Binary" presentation, BSides Canberra 2023; estimate by author assuming same rate of discovery..

Using the stricter definition, the number of zero-day exploits has increased nearly every year of the past five years, from a dozen in 2018 to 41 in 2022. In 2021, Apple and Android initiated a policy of disclosing when a patched vulnerability was already being used in the wild causing a surge in documented zero-day attacks, according to Maddie Stone, a security researcher with Google's Threat Analysis Group (TAG).

Data from Google's TAG showed that the number of zero-day exploits detected in 2023 had hit 42 by the end of September, suggesting a surge into the high 50s for 2023, a year-over-year increase of about a third. On its own, the team has discovered 16 in-the-wild zero-daysin 2023—most of which have been used by companies peddling spyware, says Stone.

While they make up the minority of attacks, each zero-day exploit has an outsized impact on industries and society as a whole, , Stone told README. The impact is worsened when attackers find a software component or product that companies may not be aware that they use, she added.

"Potentially some of these products may not have issued regular security patches to begin with, and so then that's just going to make them a much riper target for finding vulnerabilities, because you haven't had decades of security research and patches going into it already," Stone said.

Good news, bad news on zero-days

The growing use of zero-days can also be thought of as a success — attackers are being forced to use zero-day exploits because attacks that have worked in the past are much more cumbersome to pull off, Stone told README. Because software companies are getting better at secure design and creating additional security boundaries in their products, attackers need more zero-days linked in an attack chain to achieve a compromise, so more zero-days does not necessarily mean more attack paths, she said.

Typically, an attack requires three exploits to achieve a compromise. An attack needs a Remote Code Execution exploit to execute tools on the targeted system, a Sandbox Escape to break out of the security of the application, and a Privilege Escalation to take control of the system. These attack chains are a complexity with which attackers a decade ago did not have to cope.

Added complexity for attackers is a boon for defenders, Stone said.

"If they were able to have the same success with less sophisticated attack mechanisms, they wouldn't be using zero-days," she told README. "So, I think in all these conversations, it's important for us to remember that attackers using zero-days is better than the alternatives of most other attack mechanisms."

The bad news, however, is that software vendors continue to do an incomplete job in patching vulnerabilities, leading to more zero-day exploits. In 2020, 25% of zero-day exploits targeted a variant of a previously public vulnerability, according to Google. In 2022, more than 40% of exploited vulnerabilities — 17 out of 41 — were variants that bypassed fixes for previously disclosed vulnerabilities.

"[W]e know that the number of variants that are able to be exploited against users as zero-days is not decreasing," Stone stated in an analysis of zero-day trends. "Reducing the number of exploitable variants is one of the biggest areas of opportunity for the tech and security industries to force attackers to have to work harder to have functional zero-day exploits."

Look beyond stopping the attacker

In the past, cybersecurity firms have urged companies to do the basics, such as mandating the use of multi-factor authentication, keeping all software up-to-date, and training employees to avoid dangerous links. Such basic cybersecurity hygiene will block 99% of attacks in any given year, according to Microsoft's Digital Defense Report 2023.

Zero-day exploits tend to bypass much of those defenses, so while companies should continue to put their focus on the basics,they should also worry about what happens after a breach. Because zero-day exploits cannot be predicted and give the attacker access to a vulnerable system, zero-day attacks are much more difficult to stop. Implementing techniques such as network segmentation and “zero trust” principles, however, can help slow down attackers, Lorri Janssen-Anessi, director of external cyber assessments at BlueVoyant, told README.

"Can you prevent a zero-day? Probably not," BlueVoyant's Janssen-Anessi said. "You can't prevent it, but you can absolutely proactively [create a] posture so that a compromise or an exploitation of your network isn't devastating — you can definitely control that."

Attacker are also constantly evolving, not just by finding more zero-day exploits, but by ratcheting up pressure on victims to pay — creating data-leak sites to publicize attacks, for example, and in one recent case, filing a complaint with the US Securities and Exchange Commission outing a victim's breach.

It's a continuous race against the attacker, Akamai's Winterfeld told README.

"They are constantly innovating and looking for what they can monetize, and what they monetize is in constant evolution," he said. "That's why it's important to focus on minimizing dwell time versus just prevention. We can't prevent the zero-day, but we can prevent the zero-day from impacting the entire network."