Attackers are on the edge. Where are defenders?

Illustration: Si Weon Kim

VPNs, virtualization hosts, secure email gateways and other network “edge” devices have become a common entry point for attackers in significant enterprise breaches. How can defenders respond?

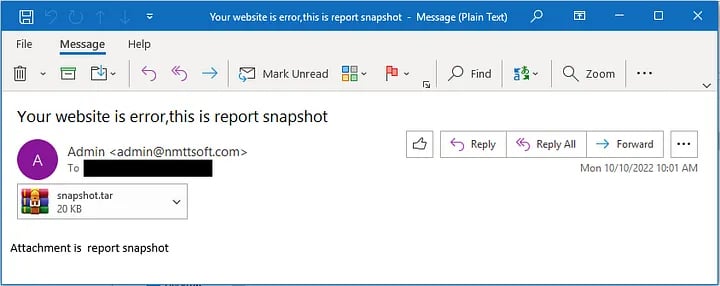

The emails looked like any other spam — many simply saying “Your website is error,this is report snapshot” — and included a JPEG image or TAR archive attachment.

Yet when scanned by the Email Security Gateway (ESG) appliances made by Barracuda Networks, the attached files exploited a zero-day vulnerability in those products. This turned the ESGs — created to protect an organization’s internal network — into a launching pad for attacks that went undetected until someone told Barracuda some customers’ devices were behaving strangely.

Mandiant attributed these attacks to a China-linked espionage group it tracks as UNC4841. According to the incident response firm’s report, the attackers exploited this vulnerability in Barracuda’s ESGs for at least seven months before the company learned of the flaw on May 18.

The state-sponsored operation highlights a trend among attackers: Targeting oft-overlooked network-edge appliances that, if compromised, give attackers a beachhead from which to extend the assault on the victim’s network.

“These devices are typically edge devices, accessible externally, and obviously have some kind of business-critical function — once you (an attacker) do find your way in, then you’ve got it made,” GreyNoise senior director of security research and detection engineering Glenn Thorpe told README. “And the fact that these are expensive devices and … are hard to get for the average researcher, means that folks that want to proactively find vulnerabilities, they have difficulty in doing so.”

The Barracuda ESG attacks are not isolated incidents. In fact, many state-sponsored hackers have shifted focus from exploiting web servers and compromising workstations — usually through phishing attacks and malware-laden emails — to often looking for vulnerable edge appliances.

A year ago, suspected Iranian government-sponsored hackers exploited a known vulnerability in VMware Horizon virtualization servers to compromise the network of a U.S. federal agency, deploying a credential harvesting tool and installing crypto-mining software, according to an incident advisory issued by the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Mandiant warned on June 13 that other China-linked attackers — a group the firm has labeled UNC3886 — had developed a toolset for compromising and remaining undetected on VMware ESXi hosts, a hypervisor for running virtual machines. And Microsoft said in April that Mint Sandstorm (an Iranian group also known as Charming Kitten) was exploiting a vulnerability in the Zoho ManageEngine endpoint and network management suite to gain access to victims’ networks.

Moving attacks to the edge

The continued focus on edge systems highlights that the most advanced attackers have put effort into compromising appliances and devices at the edge, benefiting from the lack of security agents on the specialized systems.

“[C]ertain state-sponsored threat actors have shifted to developing and deploying malware on systems that do not generally support EDR such as network appliances, SAN arrays, and VMware ESXi hosts,” Mandiant said in the blog post analyzing attacks on VMware ESXi hosts, adding that the company “continues to observe UNC3886 leverage novel malware families and utilities that indicate the group has access to extensive research and support for understanding the underlying technology of appliances being targeted.”

Infrastructure appliances and IoT hardware typically do not run any sort of host-based security agent. In many cases, the devices are highly tuned and have custom software, while in other cases, the hardware does not have the processing capability to handle additional security monitoring and controls, Ben Read, director of cyber espionage research at Mandiant, told README.

“They tend to be custom devices — or in the case of routers, they’re using a different architecture — and they don’t have the sort of underlying operating system that the agents are designed to run on,” he said. “It may be running on ARM. It may be running an architecture where the option to run an agent just does not exist, or for legitimate intellectual property reasons, the devices themselves are very locked down, where you do not have the ability to run arbitrary apps.”

Yet, both vulnerability researchers and attackers have scrutinized edge devices more closely over the past five years. Vulnerabilities have increased across several classes of devices, such as routers, virtual private networks and virtualization servers, according to data collected by NetRise, a firmware security company. While vulnerabilities — and exploitation of those flaws — go back decades, attackers’ focus has resulted in a surge in security issues, said Thomas Pace, co-founder and CEO of NetRise.

“People act like this is like a new attack vector, when in fact it’s the oldest one, it’s the very first one,” he said. “The problem has been that no one has really taken the time and energy to unravel all of this, because it’s just a significantly harder problem than traditional devices and requires significant automation and reverse engineering and binary analysis.”

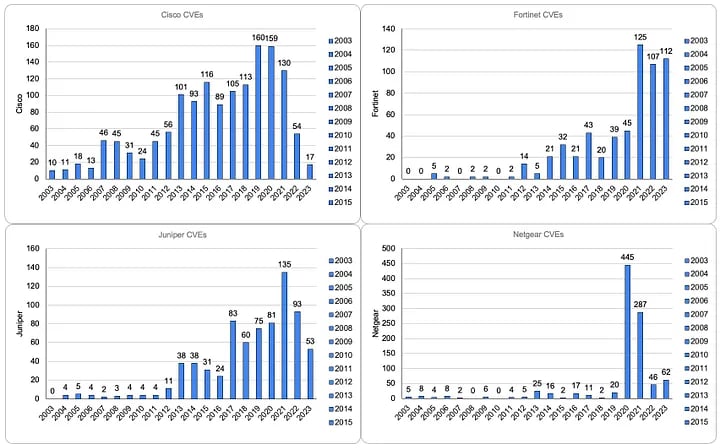

The data shows that researchers’ — and attackers’ — scrutiny is paying off. Vulnerabilities in Cisco routers, for example, peaked in 2019 and 2020, flaws in Juniper peaked in 2021 and Fortinet has seen its highest number of reported vulnerabilities over the past three years, with 2023 likely to set a new record for the vendor.

Putting host-based agents in place, however, may only be an option on some devices, said GreyNoise’s Thorpe. Network appliances, such as routers and security gateways, could add more processing power to allow for the capability to run additional security controls, but smaller connected devices are too limited for that countermeasure.

“These devices are so specialized, that it makes security controls on controls is difficult — these devices have to be so highly tuned for their function that they’re running either a specialized operating system, or they’re running an operating system that’s been altered in certain ways,” he said. “And, and by doing that, now suddenly, controls that would have worked or could have worked, now they can’t work.”

Not just infrastructure appliances

While the infrastructure and appliances at the enterprise edge have always attracted attackers, the coronavirus pandemic — and the shift to remote work and the cloud-native infrastructure that enables it — led to even greater scrutiny of the devices that define and protect the edge. Remote workers’ increasing use of virtual private network (VPN) appliances resulted in a surge of attacks on those devices in 2020 and 2021. More recently, email gateway appliances and managed file sharing services, which connect remote workers and businesses, have also been targeted.

All of these devices offer attackers and opportunity to bridge the divide between the internet and the internal corporate network, GreyNoise’s Thorpe told README.

“Generally speaking, attacks [targeting network-edge devices] definitely went up when people went remote,” he said. “And then it’s just kind of stayed there, because it’s working, and it’s working really well, and the attackers really haven’t needed to find or focus a lot of their time and energy efforts on a new or even legacy attack chains.”

Edge devices are an attractive combination for attackers. IT departments often overlook the devices during patching cycles, or at least put a lower priority on patching these products, and the devices have significant functionality. Routers, firewalls, and email security gateways, for example, can be used to connect to, or push malware to, any internal device.

And edge devices are proliferating, including not only routers and firewalls, but increasingly appliances or containerized applications that manage the enterprise Internet of Things or operational technology. While Russian cyberattacks on Ukrainian targets, for example, resulted in wiper payloads deleting critical data and bricking hardware, keeping a compromise on an edge device often allowed attackers to come back later and continue the attack, Mandiant’s Read said.

“The edge devices have a utility in more disruptive operations, because you’re not necessarily wiping the routers, but using them to maintain persistent access while conducting an attack,” he said. “If you have backdoors on a normal system, and you wipe all the systems, you wipe your backdoors as part of it, but the edge devices give you continued access.”

Organizations need more visibility

A more general approach is to increase monitoring of the traffic for the devices and look for anomalous behaviors. Defenders only detected the zero-day exploit against the Barracuda Email Security Gateway after discovering anomalous traffic coming from the device.

This sort of approach is even more appropriate for operational-technology hubs and hypervisors, which may not be able to have in-depth host-based security measures, said Jori VanAntwerp, CEO and co-founder of SynSaber, an industrial cybersecurity and asset-monitoring firm.

“Visibility at the edge is near zero in most, most environments,” he said, adding: “The fear factor is that we just don’t know, there’s literally — it could be a squirrel, it could be a misconfiguration, it could have been human error, or it could have been a cyberattack. There’s no way for us to tell at this point in time, in most environments.”

That need for visibility also extends to the software components that make up the operating systems on the devices as well, said NetRise’s Pace. Often the patched version of these systems have more vulnerabilities than older versions, because they are incorporating insecure open-source components into the code.

“With the software comes additional potential vulnerabilities that exist as part of those open-source components,” he said. “You need the visibility, because that helps you understand what vulnerabilities exist.”