Russia-Ukraine cyber conflict splits APT groups, raises threat level

The global cyberthreat landscape has changed since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but not necessarily in the ways predicted.

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the military campaign had significant support from multi-pronged cyber operations aiming to sow misinformation, shut down communications and disrupt critical infrastructure.

In the runup to the invasion, Russia-linked actors attempted to undermine confidence in Ukraine’s government and financial institutions, targeting banks with distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and sending SMS messages that claimed ATM services had been thrown into disarray. On the day of the invasion, Russian cyber actors disrupted communications in Ukraine and Europe using a destructive attack on tens of thousands of satellite Internet modems managed by U.S. telecommunications firm Viasat. As the conflict dragged on, hacktivists and Russian agencies spread misinformation through a variety of channels, and attacks against non-belligerent states grew quickly.

More than a year later, however, experts conclude that Russia has largely failed to succeed in its cyber operations, much as the country has failed to deliver a short, victorious conquest of Ukrainian territory.

Luke McNamara, principal analyst with intelligence group at Mandiant, part of Google Cloud, told README that the current war will be studied as the first major conflict with a significant cyber component.

“In thinking what the future of cyber-enabled conflict looks like, without trying to create too much of an Armageddon-like scenario, realistically, it may look a lot closer to Russia’s usage in Ukraine,” he said, while cautioning against extrapolating too much from a single conflict. “It’s wiper malware like CaddyWiper — things that are very, very basic, but that can cause potential disruption, but with limited effects.”

The attacks confirmed assessments that Russia intended to support its military invasion with cyberattacks on infrastructure and disinformation campaigns. Yet, unlike Russia’s successful misinformation campaign during the US election season in 2016, or the NotPetya crypto-wiper attack in 2017, the effectiveness of Russia’s cyberattacks have largely been blunted.

“In [the first half of] 2022, Russian cyber focus was on disruptive operations to suppress Ukrainian resilience, but they struggled to achieve this goal due to Western partners and Ukrainian organizations working closely together to quickly identify and block such attacks,” cyber authorities at the State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection of Ukraine said in a report on Russia’s cyber tactics published on March 8.

Still, organizations shouldn’t let their guard down, based on the U.S. intelligence community’s annual threat assessment released the same day. It found that Russia may grow more reliant on cyberattacks as its ground forces are worn down by the Ukrainian army.

“The Ukraine war was the key factor in Russia’s cyber operations prioritization in 2022,” the worldwide threat report said. “Although its cyber activity surrounding the war fell short of the pace and impact we had expected, Russia will remain a top cyber threat as it refines and employs its espionage, influence, and attack capabilities.”

Defense matters in a global cyber conflict

A large part of Russia’s failure is likely not accounting for the increasing effectiveness of defenders, Kenneth Geers, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council, told README. Due to the remarkable cohesion of the western alliance, the cyber component of the conflict has not caused much collateral damage on an international scale, he said.

“This war is not a story of cyberattack, but of cyber defense,” he said. “This war should convince nations that cyber defense can win — especially in the context of working with the EU/NATO alliance.”

The support from other nations in the defense of Ukraine has turned the local conflict into a global cyber theater of war. In the year before Russia invaded Ukraine, Moscow set the stage for their cyberattacks with a 250% increase in phishing attacks directed against Ukrainian users, compared to 2020, according to Google’s Fog of War research report. Yet, those attacks were significantly outnumbered by Russian actors’ attacks on NATO countries, which increased 300% in 2022, according to the report.

The data highlights that even though the military conflict is localized to Ukraine, the cyber impacts are far more wide-ranging, Google Cloud’s McNamara said.

“A lot of the targeting we saw outside of Ukraine was focused on those NATO member states,” he said. “Trying to understand through cyber espionage, the diplomatic and military strategies of organizations and countries supporting NATO.”

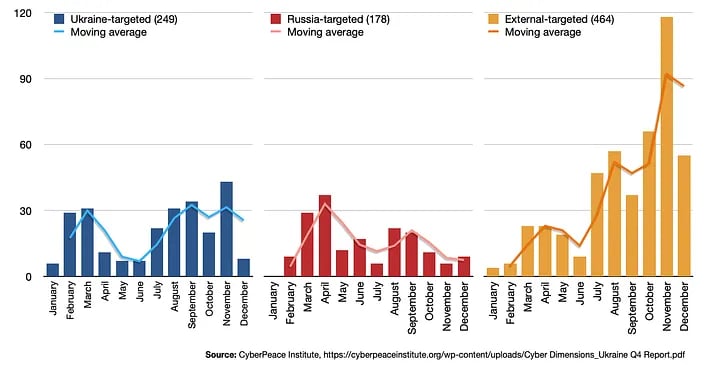

Data from the CyberPeace Institute, a cyber-conflict analysis group, shows the global impact of the war. In 2022, Ukraine suffered nearly 250 cyber incidents, with 27% of occurring during the first quarter of the year, and after a lull in the second quarter, activity ramped up in the latter half of the year, according to tracking conducted by the institute. Yet attacks on organizations and government agencies outside of Ukraine quickly increased throughout 2022, dominating the landscape in the fourth quarter.

Early focus on access, destructive attacks

A select few cyber events have been milestones in cybersecurity history: The APT1 industrial-espionage campaign conducted by China, the Stuxnet attack attributed to the US and Israel, the WannaCry destructive worm attributed to North Korea, and the NotPetya worm attributed to Russia. All have helped set the bar for what nation-states can achieve in their cyber operations, James Campbell, CEO of cloud incident response firm Cado Security and former assistant director of operations at the Australian Signals Directorate, told README.

Russia appears to have focused on gaining access to systems in the run up to its invasion. Moscow then used destructive attacks to disrupt Ukraine’s infrastructure. In the first four months of 2022, more destructive attacks targeted systems and infrastructure in Ukraine than in the previous eight years, with little collateral damage outside of the country, according to Google’s Fog of War report.

The destructive attacks are a continuation of Russian policy of targeting Ukrainian government agencies and infrastructure, with NotPetya initially targeting a Ukrainian accounting firm in 2017 before going on to cause an estimated $10 billion in damage globally. Two attacks on the Ukrainian power grid in 2015 and 2016 by the Sandworm advanced persistent threat (APT) group were also paired with wiper malware to erase some systems.

“Much like ransomware for cybercrime groups, wipers have become a favored tool of APTs,” Campbell said. “They are often leveraged against strategic targets, such as news agencies, communications platforms and the energy sector, often to devastating effect.”

Overall, however, the cyber defenses of Ukraine and its global allies appear to have blunted most attacks. While at least six unique wipers — some with multiple variants — were used against Ukrainian organizations and infrastructure, they were only initially successful and never as impactful as previous attacks, Google stated in its Fog of War report.

“The willingness to prioritize destructive attacks at the cost of persistent access indicates their importance to Russia’s overall strategy in Ukraine or the lack of operational preparation that could have sustained some persistent accesses while burning others during destructive activity,” Google stated in its Fog of War report.

While a surge in collateral damage as result of the conflict is not yet apparent, the re-emergence of Industroyer — dubbed by many as Industroyer2 — is concerning, Tom Winston, director of intelligence content at industrial cybersecurity firm Dragos told README. The malware framework was first deployed in 2016 to temporarily knock out power to parts of the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv.

A related threat — known alternatively as PIPEDREAM or Incontroller — targeted industrial control systems and operation technology and added cross-platform and native communication in common protocols used by industrial control systems.

These sorts of infrastructure attacks should be worrisome, Winston said.

“Any adversary who is devoting financial and technical resources to research and developing ICS focused malware that can have a broad impact poses a threat to any nation’s security,” he said. “Any information operations that lead to the denial of basic life necessities like, power, water and heat for any group of people pose a serious threat to civilization.”

Infrastructure and industrial operators across every vertical should keep watch for destructive attacks, and increase the cadence of defensive exercises, such as table-top exercises and risk-based vulnerability reviews, Dragos’ Winston told README. In addition, organizations should continue to build out a defensible architecture, secure remote access, and extend visibility to all OT assets in the industrial environment.

“The conflict is far from over, and we don’t know what threats yet remain as this conflict continues,” he said.

Disinformation, hactivism surge

Another major trend to emerge from the cyber conflict is an increase in Russia-aligned and Ukraine-aligned hacktivist groups openly targeting government and private companies. In the last three months of 2022, 91% of all attacks against Ukrainian targets came from hacktivist groups, while an increasing number of attacks against Russia also came from hacktivist groups, including Russian dissenters, according to the CyberPeace Institute.

In March 2022, the maintainer of the “node-ipc” JavaScript project updated the component with code that would overwrite files on systems with Belarussian and Russian IP addresses. In October, the IT Army of Ukraine allegedly conducted a cyberattack against the regional power grid serving St. Petersburg and the Leningrad oblast, although the impact of the attack has not been confirmed.

The IT Army of Ukraine has grown in size and reach during the conflict, Kurt Baumgartner, principal security researcher of Kaspersky’s Global Research and Analysis Team, told README.

“Some hacktivist groups [have] received the official backing of governments,” he said. “This backing, however, expanded on the group’s popularity but not necessarily developed the sophistication of their attacks.”

Hacktivist collectives are not the only organizations to take sides in the war.

Numerous organizations have given support to Ukraine, as part of the Cyber Defense Assistance Collaborative, which formed in March and consists of more than a dozen companies donating time and technology to help Ukraine’s cyber defenders. Google, for example, has donated 50,000 Google Workspace licenses for the Ukrainian government, a mobile alert system for Android phones, and expanded their Project Shield DDoS protection to Ukrainian organizations.

The private sector will likely take a large role in supporting defenders in future cyber conflicts.

“It is clear cyber will now play an integral role in future armed conflict, supplementing traditional forms of warfare,” Google warns in its Fog of War report, adding that it hopes companies will heed the “call to action as we prepare for potential future conflicts around the world.”